Establishing a Sense of Belonging

Establishing a Sense of Belonging

BONDING, and the Missionary Task

Establishing a Sense of Belonging

Establishing a Sense of Belonging

E. THOMAS AND ELIZABETH S. BREWSTER

Reference: Brewster, E. T. B. E. S. (1982). Bonding and the Missionary Task. Pasadena, CA, Lingua House.

We have a new little boy who was recently born into our home. In preparing for Jed's natural childbirth at home we were introduced to the concept of bonding.

In the animal world it is called imprinting. Most of us remember the picture in our college psychology books of the Nobel Prize winning naturalist Konrad Lorenz being followed by his ducklings. At the critical time, right after hatching, Lorenz and the ducklings were alone together and, from then on, they responded to him as though he were their parent. The imprinted duck experiences a sense of belonging to the man.

More recent studies supporting the concept of bonding have been carried out with a variety of animals, including goats, calves and monkeys. In each case, the infant and mother have an early period of sensitivity right after birth. If mother and infant are together at that time, a close bond results which can withstand subsequent separations.

But, if infant and mother are separated immediately after birth, the infant can become attached to a surrogate or substitute mother

- a cloth doll, a different adult animal or

even a human. If infant and mother are later reunited, one or both may reject the other or at least not respond to the other with normal attachment.

Studies of human infants and mothers show the importance of bonding. Apparently, just after birth, divinely-designed psychological and physiological factors in the newborn uniquely prepare him to become bonded with his parents.

Certainly the excitement and adrenalin levels of both the child and his parents are at a peak. The senses of the infant are being stimulated by a multitude of new sensations. The birth is essentially an entrance into a new culture

with new sights, new sounds, new smells, new positions, new environment and new ways of being held. Yet, at that particular time, he is equipped with an extraordinary ability to respond to these unusual circumstances.

People who support home birth are concerned about the bonding process between parents and the infant. An important collection of research studies published in Maternal Infant Bonding by Klaus and Kennell (Mosby Co., St. Louis, 1976) is widely read. It is pointed out that the non-drugged newborn is more alert during the first day than at any time during the next week or two. This was our experience as our son was full of interest and curiosity for his first six hours, then, after sleeping overnight, he continued, very alert for a few more hours, then he slept for much of the following two weeks.

These alert hours immediately after the birth are the critical time for bonding to occur for a sense of belonging to be established.

Typical American hospital birth is not conducive to normal bonding for two reasons. Hospital-born babies are usually drugged - groggy from a variety of medications typically given to the laboring mother. Neither the baby nor mother, then, has an opportunity to experience the period of acute alertness immediately after birth.

The other reason normal bonding does not occur within the hospital establishment is that the baby is typically snatched away from his family and straightway placed in the isolation of the nursery.

When normal bonding does not occur, rejection can result. It has been demonstrated, for example, that child abuse occurs far more frequently with children who were born prematurely and then isolated from the mother for even a few days while being kept in incubators (Klaus and DKennell, pp. 2-10).

Our desire to be intimately together as a family and away from institutional commotion in order to maximize the bonding opportunity for all three of us (father included) was a major reason for choosing home birth.

The Missionary Analogy*

There are some important parallels between the infant's entrance into his new culture and an adult's entrance into a new, foreign culture. In this situation the adult's senses, too, are bombarded by a multitude of new sensations, sights, sounds, and smells

-

but he, too, is able to respond to these new experiences and even enjoy them. Just as the participants in the birth experience, his adrenalin is up and his excitement level is at a peak. Upon arrival, he is in a state of unique readiness, both physiologically and emotionally, to become a belonger with the local people in his new environment.

But then...

Just as the infant is snatched away by the hospital establishment and put into the isolation of the nursery, so the newly-arrived missionary is typically snatched away by the expatriate missionary contingency and, thus, isolated from his new language community.

He is ready to bond -

to become a belonger with those to whom he is called to be good news. The timing is critical. Ducklings do not become imprinted at any old time. Imprinting occurs at the critical time. Bonding best occurs when the participants are uniquely ready for the experience.

* The scientific validity of analogy in understanding human behavior is widely accepted. Interestingly, in his acceptance lecture for the 1973 Nobel Prize, Konrad Lorenz chose as his topic: The value of analogy as a source of knowledge. In his book On Aggression (Harcourt, Brace & World, 1963) Lorenz makes extensive use of analogy as he studies parallels between human and animal behavior.

The way the new missionary spends his first couple of weeks in his new country is of critical importance if he is to establish a sense of belonging with the local people.

It is not uncommon for a baby to become bonded with hospital personnel instead of with his own parents. The baby then cries when with the mother, and is comforted by the nurse. New missionaries, too, tend to become bonded to the other expatriates rather than to the people of the new society. It happens subtly, maybe while

the newcomer is subject to the hospitality of an orientation time.

'When his sense of belonging is established with the other foreigners, it is then predictable that the missionary will

carry out his ministry by the "foray" method

-

he will live

isolated from the local people, as the other foreigners do, but make a few forays out into the community each week, returning always to the security and isolation of the missionary community. Without bonding he does not have a sense of feeling at home within the local cultural context. Thus, he does not pursue, as a way of life, significant relationships in the community. When normal bonding is not established, rejection of the people, or even abuse, can

occur -

it is often reflected in the attitude behind statements

like "Oh, these people! Why do they always do things this way?" or "Somebody ought to teach them how to live!" or "Won't these people ever learn?"

Implications of Bonding For the Missionary Task

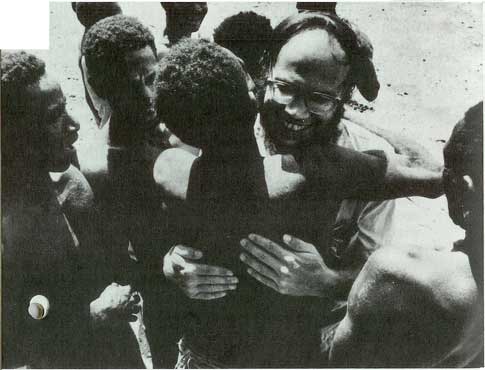

A missionary is one who goes into the world to give people an opportunity to belong to God's family. He goes because he, himself, is a belonger in this most meaningful of

relationships. His life should proclaim: "I belong to Jesus Who has given me a new kind of life. By my becoming a belonger here with you, God is inviting you through me to belong to Him."

The missionary's task thus parallels the incarnational model established by Jesus Who left heaven, where He belonged, and became a belonger with humankind in order to draw people into a belonging relationship with God.

We are convinced that the normal missionary newcomer is ready physiologically, emotionally and spiritually to become bonded with the people of his new community. Fulfillment of this unique readiness must be initiated at the time of arrival.

The timing is critical.

During his first couple of weeks, the newcomer is uniquely able to cope with and even enjoy the newness of a foreign country and its language. There have been months or even years of planning, and his anticipation, excitement and adrenalin are now at a peak.

The newcomer who is immediately immersed in the local community has many advantages. If he lives with a local family, he can learn how the insiders organize their lives, how they get their food and do their shopping and how they get around with public transportation. During the first couple of months, he can learn much about the insiders' attitudes and how they feel about the ways typical foreigners live. As he experiences an alternative lifestyle, he can evaluate the value of adopting it for himself and his own family. On the other hand, the missionary whose first priority is to get settled can only settle in his familiar Western way, and once this is done he is virtually locked into a pattern

that is foreign to the local people.

Culture shock is predictable for the missionary who has not bonded with the local people of his new community, but it is much less likely for the bonded person. The one who feels at home does not experience culture shock.

In our first culture it comes naturally for us to do things in a way that works. We know which way to look for traffic as we step off the curb, how to get a bus to stop for us, how to pay a fair price for goods or services, how to get needed information, etc., etc.

But, in a new culture, the way to do things seems to be unpredictable. As a result, newcomers experience a disorientation which can lead to culture shock.

The new missionary who establishes his sense of belonging with other missionary expatriates has his entry cushioned by these foreigners. It is generally thought that this cushioning is helpful for the adjustment of the newcomer, whose arrival is often planned to coincide with a field council pow-wow.

We would like to suggest, however, that this cushioning is an unfortunate disservice, because during the first two or three weeks the newcomer would have been especially able to cope with the unpredictable situations encountered in the new culture. Indeed, he might even revel in all the variety. But the critical first few days are the only time such a response is likely. The way these days are spent is, therefore, of crucial importance - and cushioning is the

last thing he needs.

The first prayer letter the cushioned missionary sends from the field will typically describe his airport meeting with the local missionaries, the accommodations provided by them, and the subsequent orientation by these expatriates. After writing about how he has been accepted by the other missionaries (one of his high priorities) he will invariably close with something like: "Our prayer request at this time is that we will be accepted by the local people." A noble desire, but, unfortunately, a concern that is being expressed about three weeks too late! - and now without a viable strategy to achieve

the goal. The initial blush of life in the new environment is now gone.

The individual who hopes to enter another culture in a

gradual way will probably fail to do so, and he may never

enjoy the experience of belonging to the people or having

them care for him.

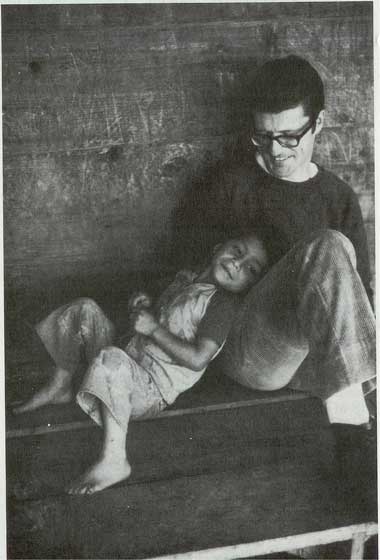

Better to plunge right in and experience life from the insiders' perspective. Live with the people, worship with them, go shopping with them and use their public transportation. From the very first day it is important to develop many meaningful relationships with local people. The newcomer

should early communicate his needs and his desire to be a learner. People help people who are in need! Then, when potentially stressful situations come up he can, as learner, secure help, answers, or insight from these insiders. (The one who is being cushioned gets outsiders' answers to insiders' situations and his foreignness and alienation are thereby perpetuated.)

A couple who has chosen to be isolated from Western people during their first months in a Muslim context wrote

to us about the victories and discouragements they have experienced:

My husband and I knew before we left that we would have different types of adjustments. I knew the hardest time for me would be at first and he felt that his hard times would occur after he had been here a while. So it has been. I really had a hard time leaving our family. But after I started getting out with the people here, my homesickness faded. The local community has so warmly received us. At Christmas, 125 of these friends came to our Christmas celebration. And during that season, the closeness of our interpersonal relationships amazed us.

The Lord has blessed our work here, and my husband is discipling two Muslim converts. We really have been alone in many ways. We supported each other but at times the burdens seemed so big and we didn't have anyone else to talk to or look to for advice. But I suppose that is why we have such good national friends.

Bonding is the factor that makes it possible for the newcomer to belong to "such good national friends." Of course there will be stressful situations, but the bonded newcomer, experiencing the wonder of close relationships, is able to derive support from the network of the local friendships he has developed. This, in turn facilitates the acquisition of the insiders' ways and gives a sense of feeling at home. The one who feels at home may feel discouraged or even melancholy for a time and some cultural stress is to be expected, but it may not be necessary to experience culture shock. Culture shock, like severe post-partum blues, may be a problem of the institutional expectation more than a problem of individuals.

It is significant to note that the new Muslim converts

mentioned in the letter above are the result of the ministry of relative newcomers. At a time when other missionaries might typically be experiencing the cushioning and isolation of a language school, those who are bonded and carrying out their language learning in the context of relationships in the

new community

also have the opportunity to pursue the

development of their new ministry from the earliest days of language learning. A few years ago the authors supervised the initial language learning for a team of eleven newcomers in Bolivia. We published an article describing that project, in the April, 1978,

Evangelical Missions Quarterly:

. . . Over 30 people came to know Christ as a result of the involvement ministry that these new language learners were able to develop during those (first) three months. Many of these were either members of the families with whom we were living, or were on a route of regular listeners. In both cases, as a result of the personal relationships that they had developed, they were able to follow up and disciple the new believers. Little wonder that this was a fulfilling experience for these new language learners. (pg. 103)

Insights gained through relationships can help to ensure, right from the beginning, that the wheels of ministry are not only turning but that they are on the ground and moving in a direction that makes sense to the local people.

Bonding and effective interpersonal ministry are realistic even for short-termers, and should be encouraged and facilitated. (The rapid international expansion of Mormonism is virtually all being carried out by short-termers, most of whom immediately move in with a local family and become belongers in the community. We were recently told by a Cantonese man from Hong Kong that the missionaries there who have learned the language best are Mormons.)

Only a minimum of the target language is needed to initiate bonding relationships. For example, we recently received a letter with the following comment: "The best thing that happened to me was on the first day when you challenged us to take the little we knew how to say and go talk with fifty people. I didn't talk with fifty, I only talked with forty-four. But I did talk with forty-four." (The 'text' she was able to say that first day was limited to a greeting and an expression of her desire to learn the language; then she could tell people that she didn't know how to say any more but she would see them again. She then closed with a thank you and a leave-taking.) The ice was broken on her very first day and, from then on, she was able to begin to feel at home in her new community.

Having local friendships is essential for feeling at home. A report developed by a mission for whom we recently consulted on a language learning project compared the 18 maximumly-involved learners with a control group of

missionaries who had been through language school. The report revealed that the individuals of the control group (the resident missionaries) each had an average of one close

national friend, while each of the learners

after only eleven

weeks

had a minimum of 15 close local friendships. Since each learner had had contacts with dozens of local people, there were at least, 1000 nationals who had had positive experiences with the learners during the weeks of the project. The report continued: "Who knows how all of this low-level public relations will ultimately benefit (the mission); it is highly improbable that it will be detrimental. 'Maximum involvement' language learning is where it's at."

Normal language acquisition is essentially a social experience, not an academic activity. As a result, gaining proficiency in the language is normal for the person who is deeply contexted and has his sense of belonging in the new society. But language study will often be a burden and frustration for the one who is bonded to other foreign missionaries.

It is therefore important to facilitate an opportunity for new missionaries to become bonded with (and hence belongers in) their new community. New missionaries should be challenged with the bonding objective and prepared to respond to the opportunity to become a belonger.

Preparation should include an orientation to the importance of bonding, with a commitment to do so. A few sentences of the new language that will be helpful for entry purposes could be learned. Also, skills should be developed in how to carryon language learning in the context of community relationships. [A recent study by Stephen M. Echerd (an in-house mission report, p. 3) included a comparison between learners that had been trained in advance and others who developed skills after arriving in the country: "Those in the group who had previous exposure to LAMP (Language Acquisition Made Practical) made 11.78 time units of progress compared to 5.82 time units of those who had no previous exposure - more than double!"]

Then, most important, from his first day he should be encouraged to totally immerse himself in the life of the new community. He should be permitted to choose to remain in isolation from other missionaries for his first few months. He should seek to worship with the people, away from churches where missionaries lead or congregate.

Our observation is that experienced but non-bonded missionaries can be a primary obstacle to the new missionary who wishes to pursue the bonding goal. We have, therefore, occasionally even recommended that a new missionary arrive about three weeks before the other missionaries expect him. One learner wrote:

The bonding concept motivated me to fly into Singapore early with no prior contacts or housing set up. This is what I wrote in my journal:

'I discovered it was actually good to be alone when breaking into a new culture - it especially adds to the expectation of what God will do! Even though I was fearful and lonely at times, I was much hungrier and eager and able to hear His voice and discern His will. And, of course, I found many who were willing to help me.'

If a newcomer is going to successfully establish himself as a belonger, live with a local family and learn from relationships on the streets, a prior decision and commitment to do so is essential. Without such a prior commitment it doesn't happen.

When we have accompanied missionary learners at the

time of their entry into other countries we have found that

prior preparation of perspectives and expectations is helpful. We therefore expect all participants in projects we supervise to meet four conditions:

1) Be willing to live with a local family,

2) Limit personal belongings to 20 kilos,

3) Use only local public transportation, and

4) Expect to carry out language learning in the context of relationships that the learner himself is responsible to develop and maintain.

A willingness to accept these conditions tells a lot about an individual's attitude and flexibility.

With a prepared mentality, a newcomer is freed to creatively respond to the bonding and learning opportunities that surround him. We have seen that with a prior decision to do so, it is almost always possible to live with a local family (though nonbonded senior missionaries are typically pessimistic). Our experience is that the new missionary - whether single, married, or even with children can successfully live with a local family immediately upon arrival. (Live-in options may be multiplied with sleeping bags.) We have seen newcomers find their own families by learning to say something like: "We want to learn your language. We hope to find a family to live with for about three months, and we will pay our expenses. Do you know of a possible family?" It would be unusual to say this 'text' to fifty people without getting at least some positive response, a mediator to help, or a family to live with.

We do not intend to imply that immediate and total immersion in a new culture is without risk. There is no time with so much stress and danger as birth; and entry into a new culture has its own accompanying stress and risk factors. It is likely, however, that the stress and risk components themselves are essential to the formation of the unique chemistry that makes imprinting and bonding possible.

And there is another side to the risk question. If one doesn't take the initial risk and seek to establish himself

comfortably within the new society, then he is opting for a long-term risk. It seems that one or the other cannot be avoided. The problem of missionary casualties suggests that there is a heavy price to be paid by those who fail to become

belongers

-

probably half do not return for a second term,

and some who do stay despite ineffectiveness may be greater casualties than those who go back home.

Indeed it is not easy to live with a family, make friends with numerous strangers and learn the language, but neither is it easy to continue as a stranger without close friendships and without knowing cultural cues, living a foreign lifestyle with all the time, effort, and alienation that that entails.

Once the new learner is securely established as a belonger

he need not relate exclusively with the local people

-

he has

not rejected either America nor Americans. (The bi-cultural apostle Paul ministered primarily to Gentiles, but when he was back among the believing Jews in Jerusalem (Acts 21) he did not reject them, but readily shaved his head, took a vow, and purified himself in readiness for a sacrifice.) The bonded missionary will probably continue to live and minister with the local people, but after the first few weeks it might not be detrimental from the bonding perspective for him to participate in occasional activities with other expatriates. It might even be helpful for him to spend occasional Saturday evenings with other learners or a supervisor (and, of course, he may seek to listen to the Superbowl with other Americans).

[The question has been raised: "What about missionaries who go to the field as a team?" A team is a team because its members share certain commitments. As a group they can decide that each will become bonded in the local culture, and they can encourage each other in the pursuit of that goal. For the initial months, a sharing time every few weeks or so should be sufficient to maintain their commitments to each other.]

The concept of bonding implies a bi-cultural individual with a healthy self-image. Bonding and "going native" are not the same thing. "Going native" generally implies the

rejection of one's first culture -

a reaction which is seldom seen and which may not be possible for normal, emotionally stable individuals. Nor is being bi-cultural the same as being schizophrenic. The schizophrenic is a broken, fragmented self. But the bi-cultural person is developing a new self

-

a new personality.

The bonding strategy and the development of this new acculturated personality can be symbolized and greatly facilitated by

taking on a new name, preferably an

insider's name. For each of us our name is closely associated

with our view of who we are

-

our self image. As we join a

new culture our goal is to develop a new self, a bi-cultural self. We need a new self that will feel at home with the people of our new culture. We need a "self' that is relatively free of our adult inhibitions, a self that will free us to fill the potential of our new roles and responsibilities.

In the Scriptures we have the record of many people whose names were changed to fit their changed circumstances. The Lord changed some: Abram, Sarai, Jacob to Israel, Solomon to Jedidiah, Pashhur to Magor-Missabib (The man who lives in terror, Jer 20:3), and Simon to Cephas which translated means Peter. Daniel and his friends were given Babylonian names: Belteshazzar, Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego. Naomi chose to be called Mara, and Saul became Paul.

We too, experience the significance of changed names in various ways: Women symbolize the belonging relationship of marriage by taking on the husband's name (we know a couple who both took a new last name, Doulos - the Greek word for servant, when they were married); Movie stars develop a new image behind a new name; In orthodox churches, vows to God are often accompanied by the novitiate receiving a new name. Even cities and countries are changing their names as they become free from colonialism or choose to identify with a different perspective. Recent changes include Zaire, Zimbabwe, Ghana, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Istanbul, Harare, and the English world calls the islands Falklands, while they are Malvinas to Spanish speakers.

Names mean a lot. Some missionaries used to require converts to take on "Christian" names: Fred, Mary, etc!. Mzee Jomo Kenyatta's first name was Kamau Ngengi. As a child in a Christian school he was required to choose a Western name. He wanted John Peter but was forbidden to choose two, so he ingeniously chose for himself Johnstone, and got the "Peter" in anyway. The name "Kenyatta" came later and served him well as the father of his newly independent country.

It will be much easier to develop a bi-cultural self image if a new name is adopted, around which the new personality can grow. We personally know many missionaries who have been given a local name as a result of talking about it with the people: Rafik (Friend) in Urdu, Dimakatso (Wonderful Surprise) in Tswana, and "Sara Child" (One who belongs to us) in Sara. Often an adaptation of one's Western name (or middle name) is sufficient if it is appropriate as an insider's name in the new society: Tomas, Marcos, etc. In some societies the use of a local kinship name might be best.

The new name with its newly developing personality does not have an established self-image to protect, and it can therefore be free to behave in uninhibited, creative, and childlike ways; it can make mistakes and try, try again. With his newly developing personality the individual can feel at home in his second culture.

For the Christian missionary, the process of becoming bi-cultural probably

begins with the recognition that God in His sovereignty does not take mistakes in creating us with our first ethnicity. Yet in His sovereignty God has stepped in and touched us on the shoulder, as it were, and called us to go and be good news to a people of a different ethnicity.

To become a belonger in a legal sense, through formal immigration, might also be considered by some serious missionaries. Immigration need not imply a rejection of one's first country, but rather acceptance of a new one. Throughout history, people have immigrated for political, economic, religious and marriage reasons. The challenge of reaching a people for Christ should have the potential to

similarly motivate some of Christ's bond-servants. The missionary's heavenly citizenship should lift him above the provincialism and ethnocentrism of a continuing allegiance to a country where, in obedience to Christ, he no longer lives. This "recovered pilgrim spirit" was the challenge presented by Joseph F. Conley in a recent Regions Beyond editorial (December 1979):

For most North American missionaries, North America is home. That is where he goes when he's sick, and when the going gets too rough he can always return to blend in with the scenery. Tomorrow the quick retreat may be cut off. We may be forced to relive those days when missionaries went abroad, never expecting to return. Many governments which refuse entry to missionary expatriates, hold the door open to naturalized citizens or colonizing communities. The Moravians led the way in this as they set up Christian colonies around the world.

Surrender of treasured U.S. or Canadian citizenship admittedly calls for a rare variety of commitment. But is that unthinkable? To such our Lord's words will find new and glowing exegesis, 'he that hath forsaken lands, . . . for My sake. . . shall receive an hundredfold and shall inherit everlasting life.'

Belated Bonding

Can a missionary w ho has lived overseas for a time without becoming a belonger

and without learning the language very well change his course? Is bonding

possible after the first critical months have passed? In the past decade our

work has carried us to over seventy countries, giving us opportunity to observe

missionary activity in many places. Only a small percentage of these

missionaries manifest the kinds of relationships with local people that would

demonstrate that bonding had occurred.

ho has lived overseas for a time without becoming a belonger

and without learning the language very well change his course? Is bonding

possible after the first critical months have passed? In the past decade our

work has carried us to over seventy countries, giving us opportunity to observe

missionary activity in many places. Only a small percentage of these

missionaries manifest the kinds of relationships with local people that would

demonstrate that bonding had occurred.

We would like to make it clear that "bonding" and "identification" are not the same thing. Maybe over 90% of all missionaries would say that they identify with the local people, but it is apparent that very few enjoy a sense of being at home with the people. It is not too difficult to tell the difference - the bonded missionaries are typically the ones who feel that even their social needs are fulfilled in their relationships with local people.

'Happiness is belonging, not belongings.' Yet the lifestyle of the majority of Western missionaries is a major deterrent to bonding. It is hard to devote time to pursuing meaningful relationships with local people when concerned about getting barrels of stuff through customs and unpacked and settled. This sense of belonging to one's belongings is a bonding of the worse kind - bondage. Unfortunately, it is a subtle bondage that is difficult to throw off. "When the farmer has got his house, he may not be the richer but the poorer for it, and it be the house that has got him." '. . . a man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone." (Thoreau, Walden)

Is it possible for an established non-bonded missionary to experience a belated bonding so that his life and ministry are then characterized by a sense of belonging with local people? The answer must be "yes" because it is a normal human process to establish belonging relationships. But we must confess that we have seldom seen overseas Americans shift their sense of belonging from their expatriate community to the people of the local culture.

Yet we believe that potential missionary effectiveness is so greatly affected by the bonding factor and by being truly bilingual and bicultural that the issue must be pursued.

Older missionaries may not be as flexible or as venturesome as younger ones, but they do have the advantage of the

perspective that comes from the passing years -

the years

that remain to give one's all in the harvest fields are all too rapidly drawing to a close. The older missionary might be more committed to making those remaining years count.

A viable bonding strategy for established missionaries again has its analogy with another divinely-ordained relationship of intimacy - the marriage relationship. This model may be helpful, for in it adult participants achieve a belonging relationship with each other. In our culture, readiness for bonding is established during the courtship; with the honeymoon, the bonding is culminated.

The analogy would suggest that an established but non-bonded missionary might release the potential of his ministry

with steps paralleling the marriage model: Acknowledge the potential and

desirability of a belonging relationship with the local people; Implement a

decision to make such a commitment to the people; then, Set a date and inform the missionary community, and any others who may affected, of the scope and implications of the potential change in his relationships. In all cultures, times of major life transition, like puberty, graduation, marriage and death, can be facilitated through festivities at the peak of emotion. The festival itself can serve to intensify the emotion which in turn can help facilitate the transition.

The commitment to belatedly join a new community

might successfully be initiated by inviting all those who might be affected to a

festive transition celebration. When the date arrives, the honeymoon analogy

suggests the necessity of becoming established with the local people by moving

in with a local family (probably in another community) and adopting a Learner role.

The mutual ownership of assets by a married couple might

suggest the need to heed Jesus' instructions to the rich young ruler. The minimum would seem to be a need for a means of reciprocity with the people. Bonding, like marriage, implies a radical adjustment of lifestyle.

The Dilemma Of the Bonded Missionary

It must be pointed out that a new missionary who pursues the bonding objective may find himself in a dilemma: his non-bonded colleagues and superiors may be threatened by the initiative he takes in pursuing his ministry through a lifestyle of relationships with the local people. His total involvement lifestyle of

ministry may contrast all too sharply with the foray excursions of other missionaries.

A few years ago we became friends with an African while he was in North America. We later had opportunity to visit him on the mission station where he worked in Kenya. In the course of our conversation he related a dilemma he was experiencing. A new missionary had arrived a few months earlier who loved the Kenyans and demonstrated it by his lifestyle. Our African friend liked the new missionary and wanted to encourage him in his relationships with Kenyans, but he was afraid to do so. Over the years he had observed that the missionaries who had not learned Swahili or the

'..11/.

tribal language

-

and hence did not relate to the Africans

- were the ones who were then advanced to administrative

positions on the station and in the mission. It was his experience that new

missionaries who loved Kenyans became an unacceptable threat to these

administrators and did not last; and he did not want to hasten the termination

of a man whose missionary approach he valued.

The bonded missionary is invariably viewed with suspicion by non-bonded colleagues. At best they may think him to be a maverick, at worst a traitor. We know those who have even been accused of losing their faith because of their efforts to make sense to the local people.

Time and again we have received feedback from new missionaries describing the resistance they experience in their efforts toward a total lifestyle approach to language learning and ministry. This resistance is expressed by other missionaries in at least four ways:

rejection, jealousy, guilt and

fear.

- Rejection may result if the bonding behavior and motives of the newcomer are misunderstood or misinterpreted. The missionary community may feel that the newcomer has rejected them. But what he has rejected is the foray approach.

-

Jealousy can arise if an established missionary observes that the newcomer has many close friendships with local people while he doesn't.

- Guilt

may occur if an established missionary recognizes that the newcomer's bonding approach may have more potential for effectiveness, particularly if he feels that he, too, should become a belonger, yet remains unable to make such a commitment.

-

Fear may surface if it appears that familiar, secure ways are going to be complicated by this new mentality. Change from traditional ways in which missionaries relate to nationals can be viewed as a movement into slippery, uncharted areas. Change implies risk and potential failure. Missionaries may also fear for the newcomer's well-being, fearing that his involvement with the people could cause him to lose the theological distinctives of their group, his own orthodoxy, or even his faith. There may be fear that he will go too far or lose his cultural identity.

Some of their fears may come true. The bonded newcomer could cause raised eyebrows in mission circles through his nonconformity. But it should be pointed out that through his bonding, and even his nonconformity, this bi-cultural missionary has the potential of an added dimension of

cultural sensitivity. It could be the very thing that might enable him to discover a redemptive analogy within the culture and pursue its implications (see Don Richardson's

Peace Child). His ability to gain an insider's perspective might also be a means of reducing the likelihood of syncretism among new believers.

Pioneer missionaries on most fields may have established belonging relationships with the people, but too often those who came after them have not followed their example and now there are few good models for young missionaries to follow. If the concept of bonding has validity for the present-day missionary task, then it seems that established missions must find ways to affirm and encourage newcomers who choose to become bonded with the local people.

The quality of relationships between new missionaries and their senior colleagues is, of course, a primary concern for all parties involved. Open lines of communication are needed. Maybe discussion about the bonding issue could give potential missionaries information that would be helpful in

developing these relationships, or even in selecting a mission agency. Prospective missionaries might initiate this interaction with both the home and field leadership of missions they consider joining.

The new missionary must communicate his concerns in an attitude of love, and refrain from condemning or being judgmental of his predecessors who have ministered faithfully according to insights available to them. The fact is that he would have probably done things in much the same way. But

new options are now open to him due to fresh insights and perspectives. A possible approach might be for him to request permission to personally experiment with a bonding strategy.

[Now that this Bonding booklet is past its second printing -

we are receiving many letters from people who have done just that -

received permission to experiment with the implementation of a bonding strategy. We are pleased that the experiences they are reporting are overwhelmingly positive. Many examples could be cited

-

here are a couple

of them:

One couple, on their way to the Cameroons, read the Bonding booklet while they were in language study in France. As a result they requested and received permission to spend their initial time in Africa with the Mricans. Upon arrival they were driven to a village some four hundred kilometers away and dropped off with their two small children. The three page, single spaced, letter we received from them was an excited account of their experiences, and an expression of deep thankfulness for the bonding concept which had enabled them to comfortably establish themselves in warm relationships with the people God has called them to.

Another couple spent their first three months in an isolated Tsonga village in

southern Africa. After eight months they are using the language comfortably and

their mission has agreed to their request to move back to that original village

where they can follow up on the ministry opportunities that were cultivated

during those first three months.]

It could be that individuals who desire to become belongers within a new community might best be able to maximize their missionary potential by volunteering for service among an unreached, or hidden, people group rather than where missions have already established traditions of non-involvement. Indeed, the present practice of many established missions in regard to bonding could be the stimulus that might propel a significant number of young North American missionaries into the thousands of remaining groups of unreached people.

By the way, we would like to make it clear that we are not arguing for uniformity and we recognize that various factors must be weighed by each missionary when considering a bonding strategy. We would argue for an experimental attitude, and we feel it is advisable to select courses of action that keep one's options open. When a new missionary family begins by becoming comfortably settled in Western accommodations the option of living in a primitive setting, or in any local way, has usually been effectively closed off for them. A choice of the more modest option at the outset is much more feasible because of the critical timing of the bonding

phenomena

-

and the option then remains open to adjust

the living location or standard if it becomes desirable. It may be useful to note that we feel that the courses of action which are chosen should not be viewed as irreversible decisions for they can be reviewed at any time.

A further advantage can now exist for the bonded belonger: as decisions are made and courses of action are reviewed, the evaluation process can be influenced from the local people's perspective. What they care about and what they think will matter to him now.

The bonded missionary, because he is a belonger, has the opportunity to gain an empathetic understanding of insiders' ways, their feelings, desires, attitudes and fears. He can listen with sensitivity to their otherwise hidden values, concerns and motives. Thus he can acquire insights and adopt habits of lifestyle and ministry that will enable him to be good news from the perspective of local people in order to draw them into a belonging relationship with God.

Bonding is therefore a perspective many missionaries may choose to value and a goal they may choose to pursue. Making this kind of significant cultural adjustment is not easy but it is possible, especially if initiated at the critical time for bonding.

In summary, we have observed that the newcomer goes

through a critical time for establishing his sense of identity and belonging during his first few weeks in a new country. If

he becomes a belonger with expatriates he may always

remain a foreigner and outsider. But at this crucial time he has the unique opportunity to establish himself as a belonger with

insiders, in order to live and learn and minister within their social context.

_______________________________________________________________________

Let this mind be in you, which was also in Christ Jesus: Who, being in the form of God, thought it not robbery to be equal with God:. But made Himself of no reputation, and took upon Himself the form of a servant, and was made in the likeness of men: And being found in fashion as a man He humbled Himself and became obedient unto death, even the death of the cross. Wherefore God also hath highly exalted Him ... That every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord.

Though I be free from all men, yet have I made myself servant unto all, that I might gain the more. Unto the Jews I became as a Jew, that I might gain the Jews; to them that are under the law, as under the law that I might gain them that are under the law; to them that are without law, as without law, ... that I might gain them that are without law. To the weak became I as weak, that I might gain the weak; I am made all things to all men, that I might by all means save some. And this I do for the gospel's sake.

_______________________________________________________________________

The authors are language/culture learning consultants and assistant professors (part-time) of Language and Culture Acquisition at The School of World Mission of Fuller Seminary (135 N. Oakland Avenue) in Pasadena, California. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Arizona; she earned hers at the University of Texas. They are the authors of how-to materials for learning languages: LAMP - Language Acquisition Made Practical, and LEARN! - Language Exploration & Acquisition Resource Notebook!.

From 1966 to 1968 the Brewsters were assistant directors of a missionary language school in Mexico. Since that time they have focused their research and work on helping missionary language

learners communicate more effectively. Their cross-cultural communication consultation and teaching has carried them to over 75 countries

during the past ten years, and has given them significant opportunity to observe and to study the relationships between expatriates and local people. Bonding and the Missionary Task is presented as a strategy to improve those relationships and to provide a basis for normal language learning (and ministry tool) in the context of social relationships.

Each summer the Brewsters teach two-week intensive pre-field orientation courses

for missionaries at the Fuller School of World Mission in Pasadena, CA. The

course content is designed to give perspective and skills for language/culture

learning and for effective cross-cultural ministry and has a primary concern to

prepare people to minister confidently and competently among unreached people. They are also available to hold seminars in various countries each year, at the invitation of mission groups.

![]() Back

to Incarnational Model

Back

to Incarnational Model